Spring 2004 – Issue 10

Spring 2004 – Issue 10

By Ethan Dezotelle

Belvidere maple producer taps into new territory

Joe Russo looks ever bit the part of a traditional Vermont maple syrup producer. From the tip of his yellow toque to his durable overalls to his heavy duty winter boots, he typifies the image of a rugged sugarer, willing to take on the elements and, if necessary, defy Mother Nature to put out a crop of quality maple syrup. He also comes off as a bit of an anachronism, dressed as he is, given the backdrop of the cutting edge sugaring operation he has built over the past few years. Standing behind his sugarhouse in Belvidere, his mustache catching flakes of gently falling snow, he reaches up and places a hand on one of seven white three-inch pipes stretching down from the Belvidere mountainside and into the sugarhouse.

“People look at these things and think it’s really something,” Russo says. “They come up here to check things out and get really excited.”

The excitement visitors to Russo’s operation, Green Mountain Maple Sugar Refining Company, feel is certainly understandable. After all, stepping onto part of what the Vermont Department of Agriculture has deemed the largest sugarbush in the state is the agricultural equivalent of “Star Trek” made real.

Tip of the iceberg

“We’re just getting started this season, “ Russo says in mid-March. “The saps trickling in, but we’re not even close to really getting going yet.”

Getting going, as far as Russo is concerned, means the healthy stream of sap currently running through the PVC pipe outside will soon becoming a rushing current of sugary goodness.

His operation has already turned out 15,000 pounds of fancy syrup in the 2004 season, but Russo expects to hit at east the 100,000 pound mark before sugaring is over. He has come a long way over the pas few years in terms of just the sheer increase in the number of taps he and his crew work with, and he isn’t finished yet.

“We’re up to 43,000 taps over 550 acres, “Russo says as he sits in the sugarhouse, warming up nest to an old, wood-burning cook stove. The aged recliner he sits in, the same one his father died in, is the one where he sleeps during a good part of the season.

“Right after this season, we’ve already got the line in to get another 10,000 taps going. Then we’ll get another 10,000 going, and on top of that there’s another 300 acre lot we haven’t event gotten into yet,” he says, the glimmer of an excited child in his eyes.

But the 63,000 taps in Belvidere are only part of the operation. There are another 5,000 taps in Coventry that have been set aside this year in deference to the tremendous amount of work to be done at the primary site.

Russo is hiring an assistant manager to work with his longtime partner, Randy Dezotelle, this year, and that person will then move up to Coventry and manage the smaller sugarbush for the operation.

The numbers themselves are a sight to behold, but they do beg the question of how Russo and company manager to turn out such a large amount of maple syrup in a year’s time.

To find the answer, it requires a trip back in time.

Growing up curious

Born in New Jersey, Russo spent a majority of his childhood in upstate New York, where he developed an early interest in the sugarmaking process.

Determined to understand how sap turns into maple syrup and even more determined to improve the process, he found himself working with the New York State Board of Education to turn sugaring season into an education.

“From the ninth to eleventh grade, the board of education approved time off from school each year so I could manage a sugar place,” Russo recalls.

In that time, he worked with the fundamentals of 1970’s era sap gathering, boiling, and product distribution. From there, he found himself in the Green Mountain State.

Russo purchased the Coventry sugarbush in 1985. Years went by and he then came across a good-sized chunk of land for sale in Belvidere. Eight years later, he has created a sugaring operation considered by some to be the most cutting-edge around.

Getting steamed

To approach the Green Mountain Maple Sugar Refining Company, one wouldn’t expect a sugar house that operates at the edge of the future.

Like many sugarhouses, Russo’s sits at the end of a dirt road that is often muddy and rutted in the spring and difficult to get to. Large and small syrup barrels are stacked at various points around the sugarhouse, waiting to be filled. A snowmobile, and all terrain vehicle equipped with a snowplow, and a couple of pick-ups sit parked outside the green sugarhouse. Old storage tanks sit off to one side, while newer ones are positioned in the back.

The biggest hint that something different, something with potential, awaits inside the set of seven six-inch, vacuum-boosted PVC pipes that zig-zag their way out of the woods before joining together and running into the sugarhouse. Each of the pipes has its own dedicated vacuum pump.

“That’s the setup that makes what we do a lot easier,” Russo says. “Every tap runs into a line, and every single one of those lines runs into one of the seven pipes. It all comes to us down here. There’s no having to go gather sap and haul it down. It does that part of the job on its own.”

There are literally miles and miles of pipe running through this Belvidere sugarbush, and the full length is checked regularly for breaks and other problems.

Once the sap is drawn down to the sugarhouse and out of the pipes, it doesn’t take long before the watery substance is transformed into maple syrup. But unlike many sugaring operations that are driven by wood fire or fuel oil, this one takes an idea from the past and brings into the present.

“We make the best possible product here by using steam, “ Russo says. “It’s a system of my own design. You can’t buy what we work with here.”

The sap is first filtered for impurities, and then it starts the reverse osmosis process. This fairly modern practice uses a high-pressure pump to force water out of the sap through a membrane. This brings the sap up to a 15 percent concentration of sugar.

From there, the sweet liquid is run into two 2,000 gallon concentrate tanks, and from there it goes into pre-heaters to prepare it for the big change it undergoes in the pan. The pre-heating brings the sap u to above-boiling temperatures.

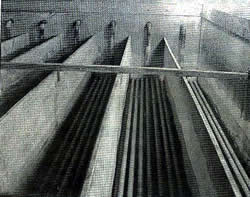

The pan is used for transforming sap to syrup is a far cry from the typical boiling apparatus that allows sugar makers to watch the sap boil while steam billows from the bubbling liquid. Russo’s is a hulking metal machine with numerous pipes running into and out of it. It suggests equally a new agricultural and industrial revolution.

Inside the pan, copper coils super-heat the sap with steam, reaching temperatures that go well beyond scalding.

“It gets so hot in the pan that it scares us,” Russo says regarding the sap as it is boiled. “When the sap hits the pan, it sounds like there’s a tiger in there. It’s just an incredible roar.”

Once the liquid turns into syrup, the sticky stuff gets drawn from the pan via an automatic draw-off system. This system calculates the boiling point of water and determines the time needed for each batch of sap to turn into syrup. Once drawn off, the syrup is pumped automatically into 55-gallon barrels.

The amount of time needed for Russo’s system to transform sap into syrup is incredibly short. In fact, seven barrels, or 385 gallons, of syrup can be produced in an hour. Russo and company have tweaked his system even further, though, and taken a time efficient machine and made it fuel-efficient as well.

Fuel oil is used to run the boilers. All the system requires to produce on gallon of syrup is less that half a gallon of fuel oil.

Behind the scenes at the sugaring operation, Russo has three boilers set up to keep the process going. There is a wood-fueled boiler, a fuel-oil standby boiler, and a massive steam boiler that fills on room of the sugarhouse, leaving only enough room to squeak around it. Russo bought the gigantic boiler, built in 1957, from Springfield Hospital in Massachusetts and had it rebuilt and brought up to current standards.

Another throwback at the sugarhouse is the method Russo employs to clean the filters the sap runs through. An old, white wringer washing machine is still cranked on during each clean-up period, not because it is the cheap or sentimental way to do things, but because it is the method Russo has found to do the best work possible.

“With all the modernization that has gone into sugaring, there is nothing out there that does a decent job at cleaning filters,” Russo said. “The wringer washers do.”

Nothing but the best

That sense of efficiency and purity is something Russo comes back to again and again as he talks about his operation.

He readily admits that “steam along will not get you quality. It’s taken many years to perfect. An operation like this has to be handled properly or it just doesn’t work. I wouldn’t do this on a large scale if I was uncertain about it.”

The level of quality he strives for involves a strong emphasis on sanitation. A large sugarbush alone does not ensure a quality product, and neither doew the method employed for making it.

“Sugarhouse sanitation is still the main focus for us,” Russo said. “When we’re done with a boil, everything is stripped down and cleaned with scalding hot water.”

The cleaning is done every time, regardless of the length of a boil. The operation doesn’t shut down in the middle of a boil, though.

Another part of the efficiency Russo seeks comes in the number of people needed to run a typical boiling period. He said in general, no more than two people need to be in the sugarhouse at any time, curious onlookers aside.

“With steam, you can work toward the best possible product,” Russo said. “It’s also the most effective use of labor, too. The hours are tremendous when the sap is really coming in, but they are really very reasonable for the amount of product we make.”

Looking to the future

Despite the size of the operation as it stands now, the potential for further growth is virtually uninhibited, at least for a few years.

With the number of taps slated to grow by 20,000 or so in the next year, Russo figures there is still another 4,00 or so taps waiting on acreage he hasn’t gotten to yet. In fact, his ultimate goal is 100,000 taps ready and waiting at the start of some future sugaring season.

Taps aren’t the only things Russo has his eyes on. In preparation for the current season, he made the move toward greater self sufficiency by installing an electric power generator “to safeguard against power outages.”

The entire sugarhouse, which has doubled in size over the last year, has been completely rewired to handle the installation of a second reverse osmosis machine. There is now a storage capacity of 100,000 gallons for sap, and he is ready for whatever the season brings.

After the last drip of sap is taken in this year, Russo will then take his operation to another level.

“We’re looking at confection. I’d like to do our own packaging and processing in that area,” Russo said, showing off an unfinished room in the back of the sugarhouse that will house confectionary portion of the business if and when it happens.

An unfinished ceiling in that room reveals a second room upstairs. When asked about it, he simply says, “That will be my apartment.”

In perhaps his greatest sign of dedication to maple syrup production, Russo intends to make the sugarhouse his home during the late-winter and early spring months, and why not. After years of sleeping downstairs in the old recliner and eating plate-sized pancakes cooked on the woodstove, the next logical step would be to simply make the facility his home.

Closing the door on the new rooms, he casts his mind’s eye further down the timeline to an idea he has been kicking around for a while.

Should everything go according to plan, Russo would like to open a pancake house at his belvedere sugarhouse. For the sugarer, cooking is as much second nature to him as making syrup. Before leaving the position last year, Russo was the director of hotel services for Holland America, a luxury cruise line. In his tenure there, he did plenty of cooking for crowds of hungry people, and he would love to translate that to the snowy, muddy woods of Belvidere.

“There’s a lot going on right now, thought,” he says. “Everything got kind of backed up with the way the operation is growing. I’d still love to do the pancake house. It would be wonderful. I’ve got to get through this season first, though, and take care of everything else. Once I get time to eat, I’ll concentrate on the restaurant.”